Portland High Schoolers Study: Media Saturation Better for Multitasking

Thursday, October 23, 2014

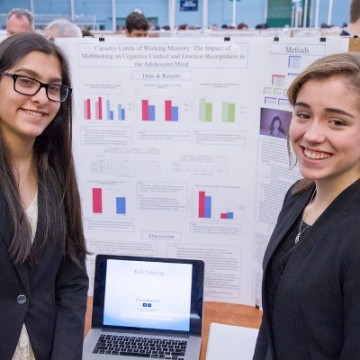

Sarayu Caulfield (L) and Alexandra Ulmer (R) with their research. Photo credit: Tom Berridge/Oregon Episcopal School

“Our acceptance email was addressed to Dr. Caulfield and Dr. Ulmer, because that’s usually who the applicants are,” said Alexandera Ulmer, who completed the study along with classmate Sarayu Caulfield.

Caulfield and Ulmer have been research partners since their freshman year through the science program at Oregon Episcopal School. Their earlier research of age, gender and media created an interest in how younger generations handle media multitasking.

“We were interested in how media affects our brains because it’s such a huge part of our lives and we couldn’t find any research on adolescents [multitasking with media],” Caulfield said.

The two studied a group of 196 females and 207 males ages 10 through 19 from their high school. Ulmer said they wanted to see how the students filtered information and switched between tasks while multitasking or not. Participants begin by answering questions about their daily media habits and taking the Stanford Multitasking Media Index which assess how often someone multitasks with media, such as answering texts, instant messages or emails at the same time.

Then they took tests that showed their ability to switch between tasks and their ability to focus on a single assignment. Participants completed the tests with no distractions or while responding to emails and counting songs, to show their multitasking skills while switching between auditory, visual and cognitive tasks.

The results showed most adolescents fell into two groups: high media multitaskers, who performed better doing multiple things or low media multitaskers, who tested better focusing on a single task. Although a majority of participants were in the later group, 60 high media multitaskers were the opposite. Students in that group spent more time using multiple media daily and scored significantly higher while taking the tests with distractions, compared to taking them without.

Caulfield and Ulmer compiled their results into the abstract Capacity Limits of Working Memory: The Impact of Multitasking on Cognitive Control and Emotion Recognition in the Adolescent Mind. They submitted it to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) this May, where they won third place for the Addiction Science Award for high school students.

Earlier this month, they were selected for the 2014 AAP Conference, the annual meeting for the organization representing 62,000 pediatricians held in San Diego. Caulfield and Ulmer’s research was selected along with 819 other abstracts through a peer-review process from 1,943 applicants. Caulfield and Ulmer were the only two high school students in the group.

“The depth of their research and its presentation was amazing considering that both girls are high school students in Portland, Oregon,” Dr. Robert Mendelson from Portland, a member of AAP who watched their presentation, said. “The result was not only interesting, but was statistically significant.”

Photo credit: iStock

However, Caulfield and Ulmer believe the difference in their results is because the subjects they tested grew up using multiple media, unlike previous studies who focused on groups who did not start using media until later on. The two believe age groups growing up with media have allowed their brains to adapt over time.

“This study suggests that digital natives (adolescents who grew up with exposure to multiple media) with high multiple media use may have developed an enhanced working memory and perform better in distracting environments than when focused on a single task with no distractions,” Ulmer said in a media statement.

Caulfield and Ulmer are currently broadening their research to test adolescents multitasking skills versus older generations while studying brain activity as well. The two think their research is important for future directions of education.

“Our findings impact school settings for generations whose education involves learning on computers,” Caulfield said. Ulmer agreed, saying in a media statement “This [research] could have a significant impact on teaching styles and curriculum.”

Related Articles

- Washington Post: Attracting Young People to Portland, Decades in the Making

- What an Oregon Professor Wants You to Know About Dread

Delivered Free Every

Delivered Free Every

Follow us on Pinterest Google + Facebook Twitter See It Read It